The Global Spread of Active Nonviolence

by Richard Deats

In the last century Victor Hugo wrote, "An invasion of armies can

be resisted, but not an idea whose time has come." Looking back over

the twentieth century, especially since the movements Gandhi and King

led, we see the growing influence and impact of nonviolence all over the

world.

Mohandas Gandhi pioneered in developing the philosophy and practice of

nonviolence. On the vast sub-continent of India, he led a colonial people

to freedom through satyagraha or soul force, defeating what was at the

time the greatest empire on earth, the British Raj. Not long after Gandhi's

death, Martin Luther King, Jr. found in the Mahatma's philosophy the key

he was searching for to move individualistic religion to a socially dynamic

religious philosophy that propelled the civil rights movement into a nonviolent

revolution that changed the course of U.S. history.

The Gandhian and Kingian movements have provided a seed bed for social

ferment and revolutionary change across the planet, providing a mighty

impetus for human and ecological transformation. Many, perhaps most, still

do not recognize the significance of this development and persist in thinking

that in the final analysis it is lethal force, or the threat of it, that

is the decisive arbiter of human affairs. Why else would the United States

continue to pour hundreds of billions into weapons even as non-military

foreign aid is cut, United Nations dues are not paid for years, and U.S.

armed forces are sent abroad on peacekeeping missions without being given

the kind of training that would creatively prepare them for the work of

peace?

Public awareness of the nonviolent breakthroughs that have been occurring

is still quite minimal. This alternative paradigm to the ancient belief

in marching armies and bloody warfare has made great headway "on

the ground" but it is still little understood and scarcely found

in our history books or in the media.

While "nonviolence is as old as the hills," as Gandhi said,

it is in our century in which the philosophy and practice of nonviolence

have grasped the human imagination. In an amazing and unexpected manner,

as individuals, groups, and movements have developed creative, life-affirming

ways to resolve conflict, overcome oppression, establish justice, protect

the earth, and build democracy.

More and more, active nonviolence is taking the center stage in the struggle

for liberation among oppressed peoples across the world. This is an alternative

history, one that most people are scarcely aware of. What follows, in

necessarily broad strokes, are some of the highlights of this alternative

history.

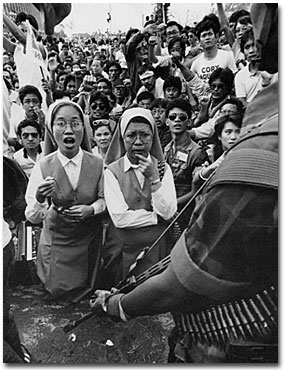

THE PHILIPPINES

In l986 millions of unarmed Filipinos surprised the world by nonviolently

overthrowing the brutal dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, who was known

at the time as "the Hitler of Southeast Asia." The movement

they called "people power" demonstrated in an astounding way

the power of active nonviolence.

Beginning with the assassination in l983 of the popular opposition leader,

Senator Benigno Aquino, the movement against Marcos grew rapidly. Inspired

by Aquino's strong advocacy of nonviolence, the people were opened to

the realization that armed rebellion was not the only way to overthrow

a dictator. Numerous workshops in active nonviolence, especially in the

churches, helped build a solid core of activists - including many key

leaders - ready for a showdown with the dictatorship.

In late l985, when Marcos called a snap election, the divided opposition

united behind Corazon Aquino, the widow of the slain senator. Despite

fraud, intimidation and violence employed by Marcos, the Aquino forces

brilliantly used a nonviolent strategy with marches, petitions, trained

poll watchers and an independent polling commission. When Marcos tried

to steal the election and thwart the people's will, the country came to

the brink of civil war. Cardinal Sin, head of the Catholic Church in the

islands, went on the radio and called the country to prayer and nonviolent

resistance; he instructed the contemplative orders of nuns to pray and

fast for the country's deliverance from tyranny. Thirty computer operators

tabulating the election results, at risk to their very lives, walked out

when they saw Marcos being falsely reported as winning. After first going

into hiding, they called on the international press and publicly denounced

the official counting, exposing the fraud to the world. Corazon ("Cory")

Aquino called for a nonviolent struggle of rallies, vigils and civil disobedience

to undermine the fraudulent claim of Marcos that he had won the election.

Church leaders fully backed her call; in fact, the Catholic bishops made

a historic decision to call upon the people to nonviolently oppose the

Marcos government. Crucial defections from the government by two key leaders

and a few hundred troops became the occasion for hundreds of thousands

of unarmed Filipinos to pour into the streets of Manila to protect the

defectors and demand the resignation of the discredited government. They

gathered along the circumferential highway around Manila which ran alongside

the camps where the rebel troops had gathered. The highway, Epifanio de

los Santos - the Epiphany of the Saints! -was popularly referred to as

EDSA. Troops sent to attack the rebels were met by citizens massed in

the streets, singing and praying, telling on the soldiers to join them

in what has since been called the EDSA Revolution. Clandestine radio broadcasts

gave instructions in nonviolent resistance. When fighter planes were sent

to bomb the rebel camp, the pilots saw it surrounded by the people and

defected. A military man said, "This is something new. Soldiers are

supposed to protect the civilians. In this particular case, you have civilians

protecting the soldiers." Facing the collapse of his support, Marcos

and his family fled the country. The dictatorship fell in four days.

Ending the dictatorship was only the first step in the long struggle for

freedom. Widespread poverty, unjust distribution of the land, and an unreformed

military remained, undercutting the completion of the revolution, Challenges

to the further development of an effective people power movement have

continued with a determined grass-roots movement working to transform

Philippine society.

LATIN AMERICA

The dictatorships that characterized Latin America in the 1980s were ended

for the most part by the unarmed power of the people. Consider Chile,

for example. The Chileans, who like the Filipinos suffered under a brutal

dictatorship, gained inspiration from the people power movement of the

Philippines as they built their own movement of nonviolent resistance

to General Pinochet. To describe their efforts, they used the powerful

image of drops of water wearing away the stone of oppression.

In l986 leftist guerillas killed five bodyguards of Pinochet in an assassination

attempt on the general. In retaliation the military decided to take revenge

by arresting five critics of the regime. A human rights lawyer alerted

his neighbors to the danger of his being abducted and they made plans

to protect him. That night cars arrived in the early morning hours carrying

hooded men who tried to enter the house. Unable to break down reinforced

doors and locks, they tried the barred windows. The lawyer's family turned

on all the lights and banged pots and blew whistles, awakening the neighbors

who then did the same. The attackers, unexpectedly flustered by the prepared

and determined neighbors, fled the scene.

Other groups carefully studied where the government tortured people and

then, after prayer and reflection, found ways to expose the evil. For

example, they would padlock themselves to iron railings near the targeted

building; others would proceed to such a site during rush hour, then unfurl

a banner saying, "Here they torture people." Sometimes they

would disappear into the crowd; on other occasions they would wait until

they were arrested.

In October of l988, the government called on the people to vote "si"

or "no" on continued military rule. Despite widespread intimidation

against Pinochet's critics, the people were determined. Workshops were

held to help them overcome their fear and to work to influence the election.

Inspired and instructed by Filipino opposition to Marcos, voter registration

drives and the training of poll watchers proceeded all over the country.

The results exceeded their fondest expectations: 91% of all eligible voters

registered and the opposition won 54.7% of all votes cast. Afterwards

over a million people gathered in a Santiago park to celebrate their victory.

In the late l980s throughout Latin America dictatorships fell like dominos,

not through armed uprisings but through the determination of unarmed people

- students, mothers, workers, religious groups - persisting in their witness

against oppression and injustice, even in the face of torture and death.

In Brazil such nonviolent efforts for justice were called firmeza permamente

- relentless persistence. Base communities in the Brazilian countryside,

for example, became organizing centers of the landless struggling to regain

their land. In Argentina "mothers of the disappeared" were unceasing

in their vigils and agitation for an accounting of the desaparacidos -

the disappeared - of the military regime. In Montevideo, a fast in the

tiny office of Serpaj (Service for Justice & Peace) brought to the

fore the first public opposition to Uruguay's rapacious junta and elicited

widespread sympathy that turned the tide toward democracy.

HAITI

Nowhere has the struggle for democracy been more difficult than in Haiti,

yet even there the people developed courageous and determined nonviolent

resistance against all odds. The people's movement is called lavalas,

the flood washing away oppression. Defying governmental prohibitions and

military abuse, the people demonstrated and marched and prayed. In l986,

Fr.Jean Bertrand Aristide was silenced by his religious order and directed

by the hierarchy to leave his parish and go to a church in a dangerous

area dominated by the military. However, students from his church in the

slums occupied the front rows of the national cathedral in Port-au-Prince.

Seven students fasted at the altar, persisting for six days until the

bishops backed down and allowed Aristide to continue working in his parish.

Then, in December l990, Aristide was elected to the presidency. Driven

from office and exiled abroad, he returned only after U.S. troops went

into Haiti.

The long term building of a democratic society there faces enormous odds.

Even though the Haitian army has been abolished, a culture of violence

remains. It will require time and persistence and the strengthening of

the grassroots movement from which a civil society will emerge, as happened

in Costa Rica where the abolition of the army was part of a larger effort

to improve education, health care, work and living conditions. Costa Rica,

without a military, remained at peace during the 1980s while much of Central

America was in turmoil.