May / June 2005

Featured Story

Living in an Extraordinary Time

By Rabia

Harris

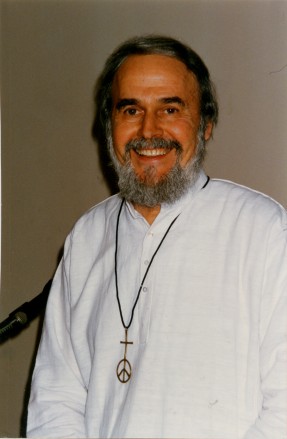

With this issue, Richard Deats is retiring as editor-in-chief of

Fellowship. Rabia Harris, interim editor, invited him to reflect on his

long career.

Harris: You are practically an institution at FOR. Just how long

have you been here, anyway?

Deats: I joined FOR on January 1, 1953 when I was a student at

McMurry University in Abilene, Texas. Muriel Lester, traveling secretary

of the International FOR, had visited the campus during a time when the

Cold War and the blacklisting by Senator Joseph McCarthy of supposed

Communists had heightened the fears and paranoia of the country. Muriel

spoke twice on campus—once on the world situation in the light of the

Sermon on the Mount, and once on prayer. The combination of the inward

journey and the outward journey she presented had an enormous impact on

me, and I decided to join the FOR. I was an active member from that time

on, as I became involved in peace and civil rights issues.

During the Vietnam war I was teaching at Union Theological Seminary in

the Philippines and was part of antiwar activities in Southeast Asia,

especially through FOR’s International Committee of Conscience on

Vietnam. Out of that involvement, FOR invited me to join the staff in

Nyack, New York. I did so in 1972. So I’ve been a staff member for

thirty-three years, as director of interfaith activities, as executive

secretary, and as editor of Fellowship magazine. That’s a long time—but

not a record. John Nevin Sayre was on staff for fifty-two years!

Harris: How did you first get

interested in nonviolence?

Deats: It goes back a long ways. As a child I was deeply

impressed in Sunday school by a picture on the wall of Jesus surrounded

by children representing the different races and nationalities of the

world. This, along with the church school teachings of overcoming evil

with good, of being a peacemaker and loving even your enemy, made me

aware of the nonviolence that permeates the teachings of Jesus.

I also learned, in that Methodist Sunday school in Big Spring, Texas,

that segregation and the racism that gave rise to it were a

contradiction of Jesus’ teachings. I would later come to see war as

another contradiction that should be opposed.

Along with my church’s teaching were the wider stirrings that were

taking place in the world. The Gandhian movement in India and the

spreading civil rights efforts in this country began to demonstrate the

practical application of nonviolence. Commitment to peace was not just

saying No (although that was important); it also led to nonviolent

action for justice and peace.

There are many who say that “the Gospel is more than the Sermon on the

Mount.” I agree—but what I have observed are Christian teaching and

practice that are a good deal less than the Sermon on the Mount. I’ve

never been convinced by those who march at the call of the nation to

slaughter the enemy and lay waste their cities and countryside. At FOR

I’ve met pacifists from Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist traditions,

and I have discovered I had far more in common with them than with

Christian apologists for war. As we find in I John 4:

Let us love one another; for love is of God, and everyone that loves is

born of God, and knows God. He who does not love does not know God, for God

is love…. If we love one another, God abides in us and His love is perfected

in us.

Dr. King spoke of this kind of love as “the key that unlocks the door

which leads to ultimate reality.” I see this in the witness of persons

like Gandhi and King, Muriel Lester and Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Desmond Tutu

and Dorothy Day, Thich Nhat Hanh and Abraham Joshua Heschel, James

Lawson and Hildegard Goss-Mayr.

Harris: What would you consider to be

the highlights of your career?

Deats: What a privilege and challenge it has been to live in an

era when nonviolence—“as old as the hills,” as Gandhi said—has spread

across the world, influencing the destiny of individuals, nations, and

peoples to overcome injustice and oppression nonviolently.

Certainly a highlight I look back upon is having been involved in the

civil rights movement and having seen the end of Jim Crow, and then

working with Coretta Scott King and serving on the Martin Luther King,

Jr. Federal Holiday Commission. It was gratifying to be in the Rose

Garden when President Reagan signed the bill making Dr. King’s birthday

a national holiday. Reagan’s initial opposition to that bill was

overcome by a determined movement all over the country—a lesson to

remember.

From the mid-1970s on, I began leading workshops around the world in

revolutionary and/or oppressive situations. One such was a trip to South

Korea at the time of the Park dictatorship. Though I was followed by the

Korean CIA through most of my visit, my hosts arranged for me to do

unannounced nonviolence trainings and speak to various audiences. It was

on that trip that I met with the Korean Gandhi, Quaker Ham Sok Hohn.

Having left the Philippines during the Marcos dictatorship, I was

invited back to help with the work Jean and Hildegard Goss-Mayr had started in aiding the nonviolent resistance

movement against Marcos. Accompanied by Stefan Merken and a group of

Union Seminary students and their faculty adviser, Hilario Gomez (a

former student of mine who later became a bishop of the United Church of

Christ in the Philippines), we met with groups throughout the island of

Luzon. These efforts contributed to the People Power movement that

nonviolently overthrew the Marcos government in 1986 and inspired

nonviolent movements in Burma, China, Chile, and other places.

Hildegard Goss-Mayr had started in aiding the nonviolent resistance

movement against Marcos. Accompanied by Stefan Merken and a group of

Union Seminary students and their faculty adviser, Hilario Gomez (a

former student of mine who later became a bishop of the United Church of

Christ in the Philippines), we met with groups throughout the island of

Luzon. These efforts contributed to the People Power movement that

nonviolently overthrew the Marcos government in 1986 and inspired

nonviolent movements in Burma, China, Chile, and other places.

Hildegard and I subsequently facilitated workshops in Hong Kong and

South Korea, as well as participating (with Jean Goss) in similar

efforts in Bangladesh, and in the first nonviolence conference in the

Soviet Union. This led to my taking FOR delegations back to Moscow and

to Lithuania for the first nonviolence trainings in both places.

Also memorable were many trips to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe,

journeys of reconciliation in places where many had thought war between

the communist world and the capitalist world was inevitable. The fright

in those early trips changed increasingly to anticipation as grassroots

diplomacy began to build up an almost irresistible tide of friendship

between East and West. As we began to be able to bring Soviet citizens

to this country, we found barriers melting and hopes for peace soaring.

We lived the truth of what President Eisenhower had said: “Someday the

people are going to want peace so much that governments are going to

have to get out of the way and let them have it.”

While the PLO was based in Tunis, it issued an invitation to FOR. Gene

Hoffman, Scott Kennedy, Karim Alkadhi and I spent five days there and

got to talk seriously with Yassir Arafat about the growing worldwide

relevance of revolutionary nonviolence. Subsequent trips to Israel and

Palestine have sought to continue this dialogue.

Certainly another highlight was the invitation of the South Africa

Council of Churches to Walter Wink and me to visit that country in 1987

and hold workshops with anti-apartheid activists. Coming at the time of

a state of emergency called by the government, it was a moment of great

difficulty for the movement there. But their determination was to lead

to the collapse of the apartheid government’s racist policies.

Harris: Of the many situations with

which you have been involved, which were most challenging? Which

subjected your ideals to the most difficult tests?

Deats: I’d have to say that what has been most difficult and

challenging over the years has been not only the reluctance but the

opposition of the institutional church to the radical nature of Jesus’

message of love even for the enemy. To always be a minority voice is an

ongoing test of one’s commitment.

On a biblical, theological, and historical level, of course, this

opposition is not surprising. Religious institutions sink their roots

deep in the culture and come to identify with “the principalities and

powers.” Any challenge to the status quo is seen not only as disloyal

but as probably heretical.

Harris: How do you see the evolution

of FOR over the years? Is it the same as it was when you started, or has

it become different, and if so, how?

Deats: First, the earliest opposition to war was principally

saying No. The refusal to kill or to sanction hatred and violence

were—and remain—indispensable to our message. But over the course of the

20th century, nonviolence became more and more central in our

understanding of how you actually live out the pacifist commitment. The

great impetus for this was the Gandhian movement, first in South Africa,

then in India.

Gandhi experimented with nonviolence as a way of life and a strategy

for change. This “experiment with Truth” as he called it has come to

have an enormous impact all over the world as individuals and groups

have struggled to overcome injustice and oppression and to build what

Martin Luther King, Jr. called “the beloved community.” FOR has been

fundamentally influenced by Gandhi’s experiments. Our current emphasis

on nonviolence training grows out of this.

Secondly, I think a major development has been FOR’s having become an

interfaith organization. Over the years and through many campaigns, FOR

discovered nonviolent traditions in other faiths producing other

peacemakers who shared its (initially Christian) opposition to war and

violence. This led to FOR’s current mission statement, which says, “The

Fellowship of Reconciliation seeks to replace violence, war, racism, and

economic injustice with nonviolence, peace, and justice. We are an

interfaith organization committed to active nonviolence as a

transforming way of life and as a means of radical change. We educate,

train, build coalitions, and engage in nonviolent and compassionate

actions locally, nationally, and globally.” Rather than watering down

faith and seeking the lowest common denominator, we have made an effort

to work for peace out of the deepest impulses and insights of each faith

tradition.

Thirdly, out of years of efforts to overcome the limits of leadership

that was predominantly white, male, and heterosexual, we have made

headway—but still have far to go—in developing a much more diverse

staff, council, and membership in the FOR.

Harris: How have your own views

changed?

Deats: Working with, and getting to know, people of other faith

traditions is an ongoing challenge, both humbling and bracing. While

still deeply committed to Jesus Christ, I have learned so much, and

continue to learn much, from those on a different faith journey. In such

a diverse world, can we do otherwise?

I think another major change has been a heightened awareness of the

environmental crisis. While this is not new, the urgency is now

inescapably upon us. Opposition to global warming in not just an option,

but a necessity. The peace and environmental movements should be much

more consciously allied in protecting the earth and humanity from the

violent direction of US foreign and domestic policies. Our current

situation is best described by Dietrich Bonhoffer’s image of being on a

train heading toward Hell.

Harris: Many people feel that to live

in accordance with an ideal requires personal sacrifice. How has your

lifetime commitment to nonviolence affected your private life?

Deats: I often think of an American nurse in Asia who was

working in a leprosarium. A visitor said to her, “I wouldn’t do this for

a million dollars.”

“Neither would I,” said the nurse.

In our money-driven society, many people link fulfillment to income.

But I cannot think of a more fulfilling life than having the privilege

of working for a nonviolent future. To get paid for that—even if it

isn’t very much!—is incomparable.

I am blessed in the fact that my wife Jan’s great commitment to music

is every bit as consuming as is my commitment to peace. Our challenge is

to keep our relationship strong in the midst of our vocational callings.

Harris: What has been most fun?

Deats: Gandhi said, “If I didn’t have a sense of humor I would

long ago have committed suicide.” I have found that one of the

characteristics of many social change movements is their sense of humor

and of finding joy even in the midst of appalling situations. I have

seen this especially in the civil rights movement and in the movements

in South Africa and the Philippines.

Cardinal Jaime Sin was head of the Catholic Church in the Philippines

during the Marcos dictatorship. The cardinal’s finally turning against

the dictatorship was of enormous importance in the People Power

movement, leading to the joke that the reason Marcos was defeated was

that he was “without Sin.” Others said, “Marcos had the guns but Cory

Aquino had the nuns.”

When the apartheid government sprayed

purple water on demonstrators in Capetown, Tutu and others found a new

motto: “The purple shall govern!” At a rally in Philadelphia,

Mississippi following the brutal killing of Goodman, Cheyney, and

Schwerner, King called on Abernathy to pray before a crowd of hostile

whites that included the local sheriff. Afterwards someone asked King

why he didn’t lead the prayer. “In that crowd, I wasn’t about to close

my eyes!” said King, to the guffaws of his friends, who were accustomed

to the humorous banter that pervaded the movement.

This is why I wrote the book How to Keep Laughing Even Though You’ve

Considered All the Facts. I thought it would be an encouragement to

people struggling against enormous odds to make this a better world. As

Texan Molly Ivins reminds us, “So keep fightin’ for freedom and justice,

beloveds, but don’t you forget to have fun doin’ it. ‘Cause you don’t

always win. Be outrageous, ridicule the fraidy-cats, rejoice in all the

oddities that freedom can produce. And when you get through kickin’ ass

and celebratin’ the sheer joy of a good fight, be sure to tell those who

come after how much fun it was.”

Harris: What is your take on the

world situation? Are you hopeful in the short run, or only in the long

run?

Deats: That’s really a tough question. To look at current

policies is to wonder if human beings have a death wish. Our assault on

the earth for short-term financial gain remains thoroughly in the saddle

in this country. Decades of important environmental achievements are

being undone by the Bush administration and its policies favoring the

richest and most predatory segments of our country. Rather than throwing

his disgraceful presidency out of office, voters were swayed by lies, by

smoke and mirrors, returning him to another four-year term.

I am reminded of the words of Joan of Arc in George Bernard Shaw’s

play St. Joan. “Some people see things as they are and ask ‘Why?’ I

dream of things that never were and ask ‘Why not?’”

Harris: What do you see as the next

steps in your life’s journey?

Deats: Well, I am in good health and still full of dreams and

energy and hope. Jan and I will continue to live in Nyack near three of

our four children and their children—as well as our first

great-grandchild.

In the immediate future I want to go through my journals and projects

and do some writing, including a few more books perhaps. I look forward

to gardening and playing the clarinet in a concert band. And I’ll be

open to some speaking and preaching, as well as perhaps a peace project

or two.

Harris: Is there anything you’d

particularly like to tell our readers?

Deats: The poet Adrienne Rich wrote, “I have to cast my lot

with those who, age after age, perversely, with no extraordinary power,

reconstitute the world.” I think of our readers and members of the

Fellowship of Reconciliation as part of this saving remnant who, in

season and out, witness to the power of truth and love to overcome all

falsehood and hatred and, in so doing, reconstitute the world.

Back to home page

|

Hildegard Goss-Mayr had started in aiding the nonviolent resistance

movement against Marcos. Accompanied by Stefan Merken and a group of

Union Seminary students and their faculty adviser, Hilario Gomez (a

former student of mine who later became a bishop of the United Church of

Christ in the Philippines), we met with groups throughout the island of

Luzon. These efforts contributed to the People Power movement that

nonviolently overthrew the Marcos government in 1986 and inspired

nonviolent movements in Burma, China, Chile, and other places.

Hildegard Goss-Mayr had started in aiding the nonviolent resistance

movement against Marcos. Accompanied by Stefan Merken and a group of

Union Seminary students and their faculty adviser, Hilario Gomez (a

former student of mine who later became a bishop of the United Church of

Christ in the Philippines), we met with groups throughout the island of

Luzon. These efforts contributed to the People Power movement that

nonviolently overthrew the Marcos government in 1986 and inspired

nonviolent movements in Burma, China, Chile, and other places.